Meeting Enrollment Goals Part 2: Common Questions

ISSUE 16

Meeting Enrollment Goals Part 2: Common Questions

By Jim Pearson and Dr. Scott Massey

Welcome back to PA Admissions Corner. In the previous Issue, we began this two-part series on meeting your enrollment goals with our 72-Hour Rule and 80/20 Rule. Now, we conclude by answering the questions PA educators ask us most often about the difficulties they face in meeting their enrollment goals.

As you know, meeting your PA program’s enrollment goals is more than placing ads, interviewing applicants, and matriculating selected students. You need a dedicated and focused approach to ensure that your PA program is structured to recruit, screen, and enroll highly qualified students. Depending on the structure and management of their admissions departments, PA programs may be competing on a lopsided playing field. Fortunately, PA programs everywhere struggle with similar issues in ensuring that their class rosters are full at the beginning of the cohort and all the way through to successful graduation.

Question: Why do some PA programs struggle to enroll 24 or 36 students per cohort, while others can always hit their numbers?

Make sure that you have aligned the timing of your admissions cycle to enable your admissions department to communicate with the largest percentage of applicants, alongside most other PA programs. This can be achieved by:

- Running an admissions cycle from April to October

- Using a rolling admissions cycle

- Interviewing early in the admissions cycle

- Sending acceptance letters early in the admissions cycle

For more detailed information on all of these strategies, look back to PA Admissions Corner Issue 3: Controlling the Admissions Cycle.

Your admissions department must always target the applicants who fit your program’s unique characteristics. Doing so is a significant factor in ensuring your PA program’s admissions enrollment goals are met.

Question: Why is it so hard to achieve enrollment goals even with abundant applicants?

Successful applicant enrollment results from a series of relationship-building steps, from the moment a prospective student submits their application until the day of matriculation.

How can this relationship be fostered?

- Early and sustained communication is paramount. Evaluate your communication process from the time of application submission through the interview process to foster a strong connection with the prospective student.

- Provide opportunities for interaction between the program director and prospective students.

- Include current students in the process. Their inside viewpoint can be invaluable to applicants.

Every applicant has an affinity group—support systems, friends, and family —who play a role in their decision, and it is naive to assume the opinions of the affinity group won’t matter. Without moving the focus away from the applicant, include the affinity group in the communication process.

- Offer resources to support relocation to the area.

- Promote a family-friendly atmosphere in your program by welcoming the affinity group into the selection process.

- Add a step in the interview process that allows the affinity group to speak with a faculty member, a financial representative, or even the program director.

Question: Why does our conversion rate from offer to matriculation seem lower each year?

Conversion rate is the percentage of applicants offered seats in your program who eventually matriculate. This percentage fluctuates considerably among programs, and there are strategies that can mitigate this variable.

By the end of their interview with your program, an applicant has most likely made up their mind whether or not they will enroll. You are going to need to ask yourself some hard questions about whether your interview process was disorganized or left the applicant feeling unwelcome. It will require some deep self-assessment. Here are some strategies that can help with this issue:

- Evaluate your interview process. It is strongly suggested that applicants get the opportunity to meet with the program director in person or virtually, depending on the circumstances. Create a segment in the interview process called, “Q&A with the Program Director.”

- Evaluate the length of time between the interview and the acceptance offer. Allowing too much time to pass will result in competitive applicants receiving competing offers.

- Consider offering the most competitive applicants an immediate seat in the program. Their application and interview are so impressive that accepting the applicant is practically assumed. Why wait? Ensure that the applicant receives correspondence via email within 72 hours. These applicants are likely to have multiple options. Don’t lose them to other programs!

- Consider whether the applicant feels informed and feels like they have been heard throughout your interview process. Or, did they leave the interview process with an uncomfortable feeling that they were put under a microscope or rushed out the door? If applicants perceive that you are indifferent to them, they will decide that your program is not the right fit. Find ways to make applicants feel welcome and able to ask questions about the program in an open and relaxed setting. Always remember that an applicant is interviewing you as much as you are interviewing them.

Question: Why can’t we fill our cohort, even though we are getting hundreds of applicants?

Programs that find themselves unable to fill their cohort despite receiving hundreds of applications most likely haven’t figured out how to manage the required human resources to operationalize an effective admissions process.

Primarily, your program must have the necessary human resources to cope with the volume of applications. For more information, see Issues 12 through 14 of PA Admissions Corner, where we discuss ways to solve the troubles of an overworked or understaffed admissions team.

You might also be wasting time interviewing applicants who have no intention of attending your program. Properly identifying the best applicants for your program from the outset can save much of this wasted time.

Question: By the time we reach out to interview applicants, they already have been selected elsewhere. How can we reach out to them first?

Fine-tune the steps in your admissions process and improve your image. Poor public relations or a disorganized interview process can adversely affect applicant perception of your program. A streamlined, student-centered admissions process will reduce the likelihood that another program will appear more attractive.

Question: How can we fill empty seats at the last minute without sacrificing applicant quality?

To fill empty seats in the last weeks before matriculating, scour the existing applicant pool for any quality applicants who can still be fast-tracked into the system. Consider a truncated admission cycle in the weeks leading up to matriculation while maintaining your standards of admission, then arrange a virtual interview.

Once a student has accepted a seat in the program, your University Financial Aid Department has to expedite their financial aid package at a moment’s notice if you’re already in the home stretch. Spare no expense to avoid an angry Dean who asks why your seats are not filled on the first day of class.

Question: How do we fill a cohort with a shallow applicant pool?

Some programs find themselves with a smaller number of applicants than the national average, especially new or developing programs accepting their first or second cohort.

You can still manage, but you have to max out on applicant outreach and incorporate all of the strategies we have discussed so far. These applicants need to be fostered and convinced that your program is the best solution. It’s especially necessary in this situation to move to a rolling admissions process so you can communicate and work with all your qualified applicants early and often.

Conclusion

Every empty seat in your cohort is a lost tuition revenue for one student, which can seriously impact your PA program’s budget. There are close to 12,000 seats nationally available for PA programs every year, and more than 34,000 applicants. With these numbers, no PA program should have empty seats on day one.

By promoting a focused mission for your admissions team, improved communication with applicants, prompt acceptance, fast-tracking ideal applicants, and increased outreach when necessary, you are doing the utmost to fill your cohort with students who are happy to be a part of it.

NEXT TIME…

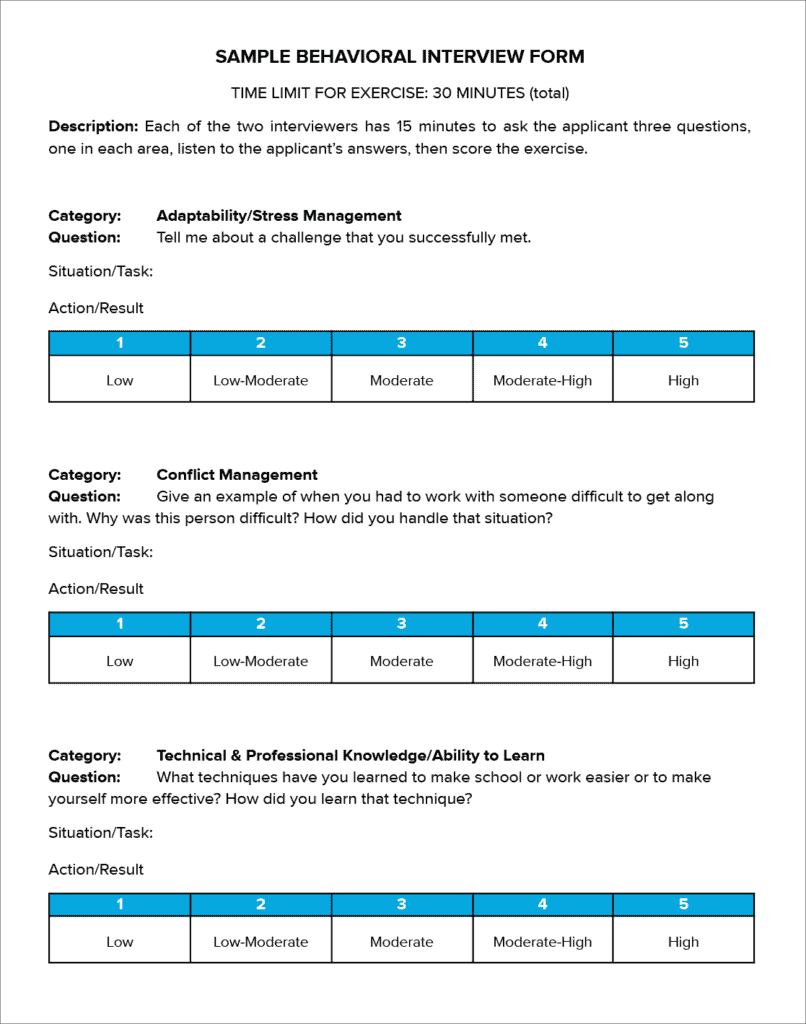

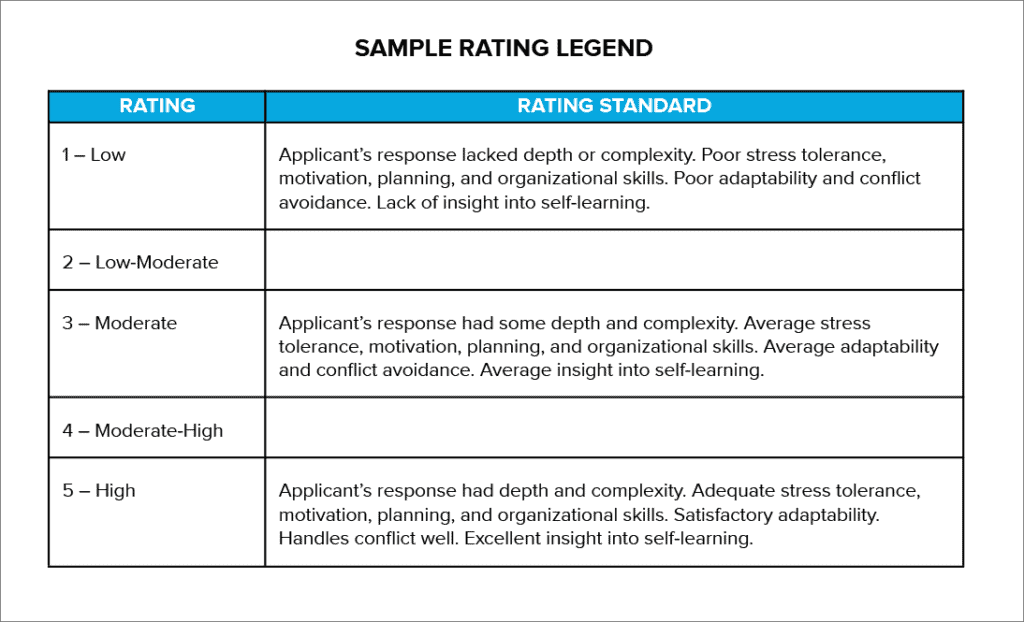

In Issue 17 of PA Admissions Corner, we’ll begin a five-part series on Successful PA Admissions, covering several topics on filling your cohorts with students who match your program’s mission and vision. forget an in-depth look at finding your ideal applicants, behavioral and group interviewing, and expanding the diversity and inclusiveness of your program.

To your admissions and program success,

Jim Pearson, CEO

Exam Master

Dr. Scott Massey Ph.D., PA-C

Scott Massey LLC

Exam Master partners with PA programs by:

- Supporting Admissions

- Strengthening Foundational Knowledge for Early Success

- Fostering a Culture of Self-Directed Learning

- Providing Targeted Remediation & PANCE Prep Resources

- Pre-Matriculation Program

- Medical Terminology

- Emory Body System Review Program

- PANCE Question Banks & Practice Exams

For information on any of the above products and/or services, contact us.